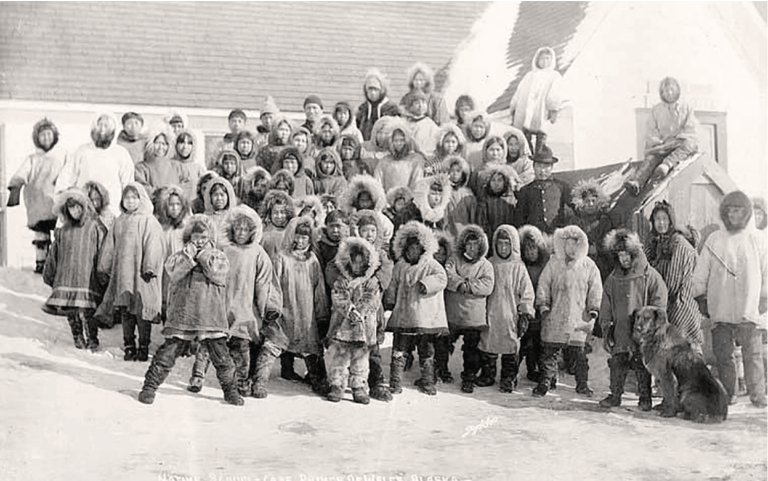

Above: Alaska Native children wearing fur parkas posed outside of a school, Cape Prince of Wales, Alaska, between 1901 and 1911. Photo by Beverly Bennett Dobbs

The Molly Hootch case, which ultimately dismantled a discriminatory education system for rural Alaska Native students, was first filed in Anchorage on August 1, 1972. The class action lawsuit was joined by 28 students and their families, who argued that their state constitutional right to an education was being violated.

For decades, secondary school students from rural Alaska Native villages were sent to boarding schools as far away as Anchorage, Sitka, or even Oregon and Oklahoma. Students suffered disconnection from their loved ones, communities, and cultures. Many reported being treated as free servants or babysitters by the non-Native families who boarded them.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs system was condoned by the state of Alaska. The case, later renamed Tobeluk v. Lind, wound its way to Alaska’s Supreme Court, where the state’s secondary school program was determined to violate the Alaska Constitution’s guarantee of education. It led to the creation of 21 rural school districts and passage of a state bond that funded the construction of rural schools.

The arrival of schools brought change to rural Alaska Native communities. Schools became community hubs, curricula came to incorporate local cultural values, and young people gained an education while staying with their families. But challenges persist today for the rural schools, including high costs, attaining afford- able technology, and incorporating Alaska Native languages and culture into lessons.

In her memoir, I Remember When, Molly Hootch Rymes recounts her youth in the Yup’ik village of Emmonak along the lower Yukon River and the circumstances leading up to the case.

Comments are closed.