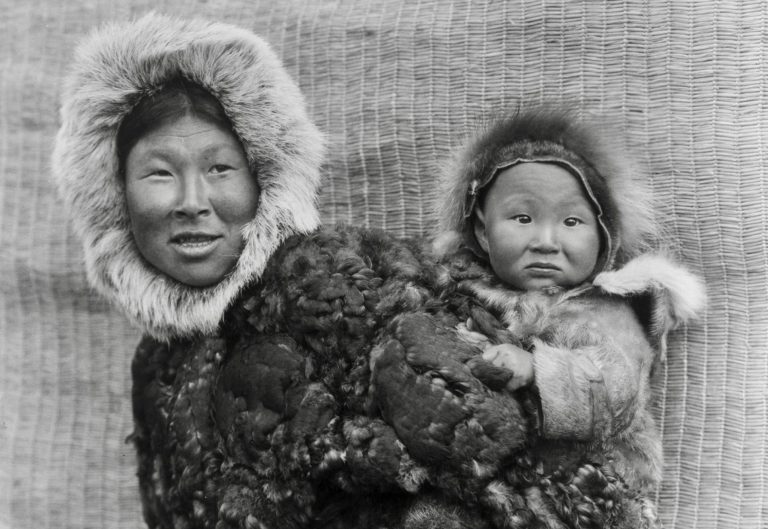

Alaska Native clothing expressed the wearers skills, wealth and ethnic identity. In this photo, a Nunivak woman wears a bird-skin parka and carries a child in 1929. Photo by Edward S. Curtis/Library of Congress.

Underendowed for high latitudes, humans, to endure and even thrive there, learned to slip into skins of creatures better suited. Step by northward step, sub-Saharan brains contrived comfier, smarter microenvironments. Functional, well designed, expertly made, such couture expressed the wearer’s skills, wealth, local or ethnic identity—it still does—and pleased the animals’ spirits.

Regional styles distinguished friend and foe. Charles Francis Hall and Vilhjalmur Stefansson braved the Arctic in garb tested over millennia. “The Needle work of these Cloths does great honour to the ingenuity of the Ladies of the Country,” Captain Cook thought, “to be excelled by no People under the Sun.” Pilots and flying game wardens donned moose hide gauntlets, caribou parkas, or all-fur flight suits and the mountaineering priest Hudson Stuck lynx-paw mitts and a beaver hat, remarking that Athabascans wore beaver “to the great advantage of health in the severe winters.” Outdoors people still consider caribou footwear and beaver mitts superior to synthetics.

Central Brooks Range Nunamiut (inland Inupiat) weather the continent’s worst cold, −55 degrees or below. Lightweight, very warm, water-resistant, and strong, caribou skins traditionally enabled them. Dense underfur trapping air under long guard hairs conserves heat, as does layering. And the honeycombed guard hairs contain tiny air bubbles, much like synthetic Hollofil fiber. In clinical trials, skin-clad subjects stayed warmer than those in expedition or army winter getups.

Centerpiece of Yup’ik and Inupiaq dress was the hooded parka. It could be worn with the fur inside and another over it, fur facing out. The word—Aleut, with Siberian roots—arrived with the last wave of indigenous colonists in small watercraft. While modern materials replaced animal hides in certain contexts, the basic parka design persists. A wolf or wolverine hood ruff’s uneven hair length creates a calm-air pocket in windy conditions, a safeguard against facial frostbite. Wolverine sheds frost condensate from exhalations. During trail tea breaks or before entering homes, travelers whapped their clothes with a caribou-antler or wooden “snowbeater,” as melting snow weakens fur’s insulating properties. Mottled, Alaskan-bred Siberian reindeer sparked an early-nineteenth-century fad of piebald apparel with striking contrasts. Women’s parkas with spacious hoods cradling babies boasted checkerboard panels offset with tassels or trims. Summer skins sometimes were preferable—shorter-haired, not as warm, they’re less prone to shedding and easier to tan. Thin, pliable calfskin yielded the best parkas, a large fall bull’s back, sturdy boot soles.

Dry grass, rabbit, or ground squirrel socks lined knee-high mukluks, caribou leg-skin boots loose enough for good blood circulation. Their wide tops let moisture escape. Skin off the backs of animals’ legs lacked thin spots caused by their kneeling. Hooper Bay’s Neva Rivers wore mukluks (from Yup’ik maklak, “bearded seal”) “all the time…except in the summertime, when we usually went barefoot or used short little boots.” Caribou skin pants and mittens completed the outfit. A skilled seamstress could make one in a month.

For milder, wetter coastal seasons between Barrow and Bethel, sealskin, lacking underfur, was ideal. Waterproof boots factored most when snow and ice became slush. Sublimely patterned, porous ringed-seal skins are durable as well as breathable. Their natural oils, preserved through a special tanning process, repel water. A stitch with sealskin sinew, which swells when wet, joined crimped, dish-like tough bearded-sealskin boot soles to “stovepipe” uppers shaved or with the fur left on. Strips sewn onto the seams also prevented leakage. Sealskin was handy too for mittens, pants, and lighter parkas. All outerwear had to fit properly; for tape measures, formerly, on St. Lawrence Island, “They use their hands from thumb to middle finger,” according to Estelle Oozevaseuk.

Where caribous were absent and minks, otters, or muskrats scarce, birds sufficed. “Water just rolls down their feathers,” the Yup’ik elder Frank Andrew recalled. Reversible parkas served differently in either rain or cold: plumage on the outside, under an optional gut shell, or against the skin. Cook in his 1778 journal reported both ways for Unalaska.

The avian target species, thicker-skinned diving birds, were netted or downed with bolas, then skinned, de-fleshed, and repeatedly rinsed. Birds ready to migrate after the fall molt provided the plushest skins. A parka of pigeon guillemots, eiders, puffins, emperor geese, or oldsquaw ducks could last two years. St. Lawrence women tailored parkas from 20 murres with whale or reindeer sinew and formfitting socks from two loon bodies. Aleut parkas incorporated 140 cormorant throat skins.

Lydia Apatiki from Gambell, who revived the obsolete craft there, likes charcoal-gray crested auklets, and white-breasted parakeet auklets for flashy chest panels. Yup’ik Day “show and tell” at their kindergarten inspired her. She couldn’t remember any islander having sewn a bird-skin parka in a long time. So, she asked an aunt how to make one for her grandson.

Kayaking and tide pool hunting required a different kind of protective gear. Kamleikas, Aleut diaphanous raincoats of bearded seal, sea lion, bear, walrus, or whale innards, surpassed European raingear before rubberized mackintoshes, and the Russians commissioned some cut like overcoats, for merchant-ship crews. First, the intestines—250 feet in a sea lion—were cleaned, inflated, and air-dried, and then split open and cut into strips. St. Lawrence Islanders hung them up in cold, sunny weather, which turned them uniquely supple and white. Even plain gut parkas took one month to finish but lasted only about five. Tightened with hood and wrist drawstrings, short ones cinched around the kayak cockpit’s coaming with a hem tie for a sprayskirt–paddle-jacket combo. Puffin beaks, feathers, dyed baby-seal fur, and colorful yarn worked into seams adorned ceremonial kamleikas. Fox gland oils impregnated sea lion-gut galoshes. Rubber ensembles after WWII replaced these Native XTRATUFs and Helly Hansen tops. They couldn’t, though, replace the pride in locally sourced, snazzy handiwork, in having envisioned and fashioned it.

Comments are closed.