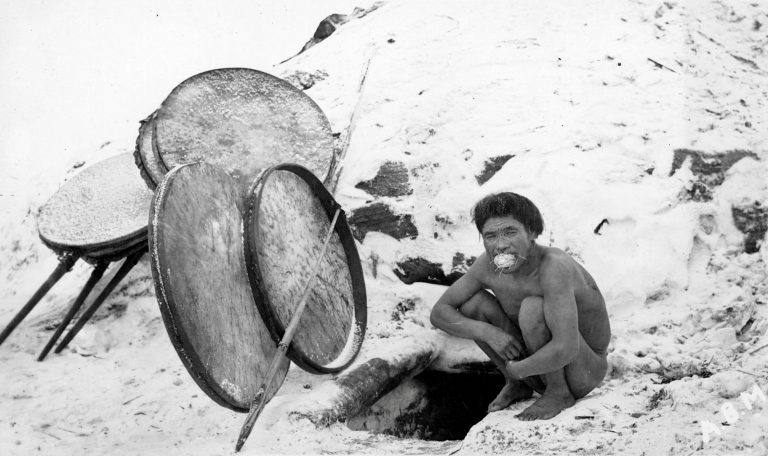

Alaska steambath culture predates Western contact. A Yup’ik man outside a qasgiq with a respirator in his mouth, ready for a firebath. Photo from John Urban Collection, Anchorage Museum, B1964.1.791

Bodies melt beaded with sweat. Hearts pick up their pace, blood vessels relax. All talk has suffocated. The 55-gallon-drum woodstove shakes and roars from internal combustion, its pipe glowing like a fighter jet’s engine nozzle. When an elder dips water onto hissing, animate rocks, dragon’s breath roils through the windowless room. The air thickens. The less stalwart lie down to escape the inferno at head height.

William Healy Dall, surveying the newly acquired territory, called this dim crucible “a great luxury” and “an institution to be proud of.” However, Dall warned, “These baths cannot be recommended for those with a tendency to heart disease or apoplexy…” Each Russian trading post since the early 1800s had been furnished with a bathhouse, and each Yup’ik Eskimo qasgiq—the men’s dorm and workshop, the community’s dance floor and church—could be turned into one.

History of steambaths in Alaska

Visitors to southwestern Alaska described Yup’ik dry “fire baths,” which differed from saunas. Closing the qasgiq entrance, Native men stoked a driftwood blaze in the central floor-pit. H.M.W. Edmonds, wintering at St. Michael in 1890, considered the heat “great and almost unendurable,” with walls hot as hell’s hinges, too hot to be touched. Loon-skin caps shielded scalps and ears from the fierce atmosphere. Woven mouth masks gripped with the teeth and filled with wood shavings protected lungs. Smoke pluming from a skylight normally lidded with sealskin informed villagers of a maqi, a sweat. Busting out naked like First Man from his peapod, bathers afterward lolled on beaches, scrubbed lobstered limbs with snow, or plunged into water barely liquid.

With the move to scattered cabins and obsolescence of the qasgiq, maqiviit mushroomed: smaller, Russian-style, log or plywood steambaths with stoves, low ceilings, and entranceways for undressing and for cooling off between rounds. Most delta homes nowadays have one, with some used nightly through almost four decades. After the men and older boys, women and children simmer at slightly less-cruel temperatures—legendary sweats reach 255 degrees. Most kass’aqs—non-Natives (from “Cossack”)—can’t face such volcanic interiors. Endurance is a matter of local pride, litmus for an outsider’s mettle. “It takes a moment to resettle,” an anthropologist rendering the flesh’s juices noted, “to begin to be able to form coherent thoughts again.” A bucket bath follows the last bout of perspiration. Soaped, shampooed, and ladle-rinsed, you’ve become a string puppet, a huge rosy baby; this deep cleansing makes the body tingly, the mind calmly lucid, a Buddha’s.

Steambath practices

The maqivik as a place for traditional medicine cures colds, arthritis, and muscle aches. Pumice, a porous lava, the best rock for “pours,” doesn’t shatter but puffs rather nicely. Pine boughs on popping rocks and self-flagellation with birch or sage switches, “thrashing,” in Dall’s words, “until all impurities are loosened from the skin,” spice the air minty-fresh and boost the sufferers’ circulation. A vital women’s retreat, this womblike space fosters the voicing of concerns, discussions of village events, teasing, and joking. The male shift also rehashes hunting exploits and traditional tales or cooks up joint projects. In winter’s steel vise especially, mental health looms large among sweating’s restorative benefits. “Something’s bothering you,” elders say, “go take a real strong steam. Then just pour it off, let it burn it off.”

Russian colonists introduced the banya, perhaps borrowing Finnish-Karelian traditions, as a novelty, many people believe. But pre-conquest Kodiak and Prince William Sound sod-houses trapped heat perfumed by angelica leaves in narrow side chambers. Village site rubble holds charred, cracked rocks over 3,000 years old. For these Alutiiq relatives of the Yup’ik, firebathing comprised religious practice. Seeking balance, warriors built up a good smother before launching raids. Women washed babies born in seclusion huts at the maqiwik before presenting them to the household. The freshly purified mothers put on new clothes and buried their old ones.

The custom thrived wherever Russians craving otter pelts sailed. Cook Inlet and Bristol Bay Dena’ina Athabaskans still favor the neli (banya) approach to wellbeing. Tlingits bent saplings into impromptu sweat lodges roofed with cotton drill or canoe sails and cupping two or three people. Miners readily embraced the wholesome vapors—the Treadwell Gold Mine’s Douglas Island rec-club boasted a natatorium with a pool, tub, shower, and steambaths. Mandatory membership cost $1 per month, soap and towels included. Native and Japanese employees, working 11-hour shifts, were excluded.

Modern steambaths

In Alaska’s “dry-cabin” and homesteading settings, modern saunas are deemed essential, more so than TVs, carports, or screened-in, mosquito-proof porches. But you can have too much of a good thing, evidently, and the Slavs’ gnomic day-spa spirit Bannik go batshit безумный on you. In 2018, Dillingham saw conflagrations from unwatched steams that cindered four banyas within eight weeks. Barrel stoves over the years bake any moisture from nearby wood, which, unlike hardcore bathers, reaches the point where temperatures well under 200 degrees induce smoldering.

Comments are closed.