To Fura Kancha Sherpa, a chip off Nepal’s Khumbu Valley, southcentral Alaska’s Talkeetna Mountains must look like mere foothills. His co-guide, Dylan, calls Fura, who’s summited Everest nine times and grew up around the animals, “a true yak whisperer.” In fact, the shy, rail-thin drover under a baldness-concealing ball cap whistles or hollers to keep them doggies rollin’.

A guest worker for the short summer, Fura greets two floatplane loads at Sheep Back, a lake headed by shark-tooth peaks in whose shadows he’s guarded seven yaks since the previous backpacking bunch flew back to Talkeetna two days ago. Crosswinds at our destination detained us in town that long, and I’d crashed at the staff house. Tomorrow, Fura will retrace his steps to Moon Shadow Lake, providing logistics for Alpine Ascents’ weeklong trekking trip—us—on the way.

We fire-chain food and gear from shore up a grassy bank. Camp has been left standing—a blue-and-white kitchen tent, a carport-style dining tent, and the yellow dome in which clients will sleep. Besides Dylan, a Washington-based, ski-patrolling seismic engineer-mountaineer with a blond beard and fledgling ponytail, there’s Piper—his well-behaved avalanche-rescue border collie—and Maren, the Talkeetna assistant who skijors with huskies and is getting her pilot’s license. A father-son pair completes our group. Alaska-virgins, both will sprout stubble here. Rick’s close-cropped white hair and good-old-boy manner befit an erstwhile Vietnam recon pilot and retired Pacific island missile-range commander. His son Eric, equally barbered, tall and buff as a quarterback, recently launched an Austin craft brewery. A frilly bicep tattoo flaunts this first-time backpacker’s love for Texas, hops, and his Brazilian wife.

Yaks in Alaska

I’m eager to meet the creatures of legendary reputation. Smart, sociable, selected for tractability, and boasting personalities like those of canines—Einsteins compared to run-of-the-mill cows—the beefy bruisers were first bred millennia ago in Tibet, from spunkier wild stock that still roam the Himalayas at 16,000 feet. They embody wealth on the hoof, the currency of survival. To this day, yaks supply nomads’ and villagers’ needs: meat, milk, and cheese; butter fueling votive lamps and potent, smoky tea; spinning fiber; tippy leather “bull” boats for stream crossings; dried-dung briquettes, cud’s blessing in treeless country. Yaks plow fields and thresh grain and compete in races. Their “ox treasure” testes boost Chinese libidos. They deliver oxygen tanks and espresso to Everest’s basecamp and in Alaska yield farm-raised steaks and wool softer and warmer than that of merino sheep. They caravanned salt, and one carried the exiled Dalai Lama to India. Divine messengers, they romp in dances and myths. Some go so many months unattended they turn semi-feral.

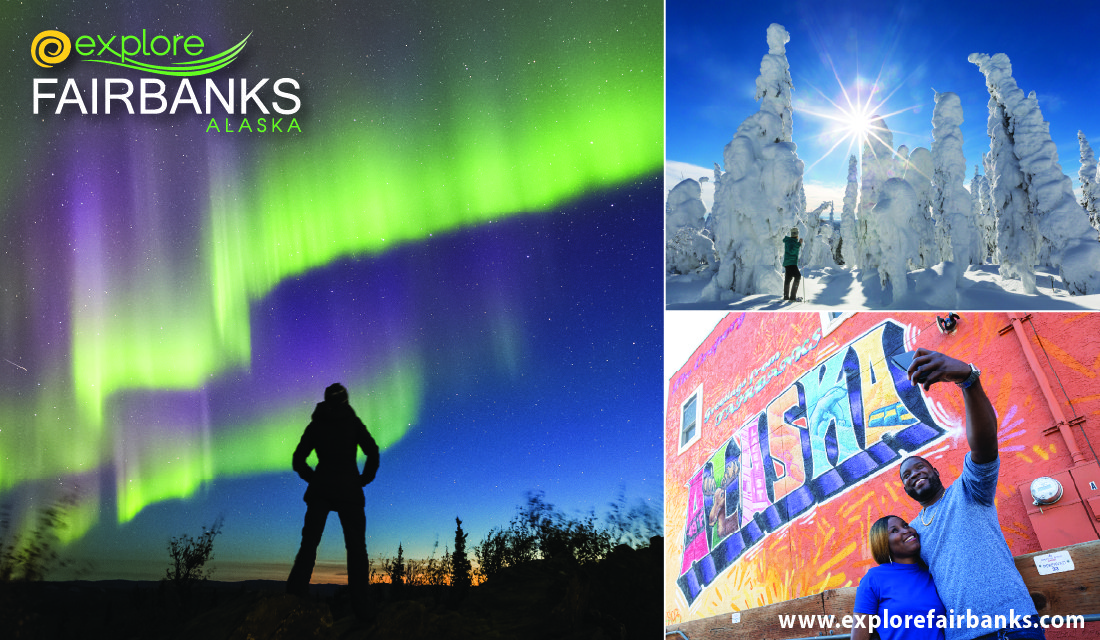

Before the Depression, Canada-born yaks in Fairbanks had been crossed with Scottish Galloway cattle to enhance the Interior’s meat production. The resulting, infertile “galloyaks” endured cold but not farm drudgery, especially being milked. According to the former director of the university’s Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station you could do it, but it wasn’t easy. Their era allegedly ended when one savaged the college president’s garden. The following winter, galloyak-heavy school cafeteria menus revealed a third drawback—the meat was tough, almost inedible.

While our piebald energy bundle sniffs ahead, nosing the burrows of ground squirrels that pop up like whack-a-moles, we explore a ridgeline, easing into amazingly bug-free surroundings. We weave uphill between star gentians and harebells, between outcrops fractured by frost and crusty with lichen from which alarmed marmots shrill. A hidden mist machine allows only glimpses of jade lakes, snow shrouds, and crumbling, gray pyramids. Clouds erase those during our return and then spatter drizzle.

Meeting the Yaks

Near camp, where fireweed slashing the landscape is its sole vivid aspect, we run into our party’s bulk, the magnificent seven. The “boys”—Jack, Joseph, Levi, and Pemba (“Saturday”)—graze haunch-to-haunch with Nima (“Sunday”), Dawa (“Monday”), and Pratima (“Trim, with a Nice Smile”). Sherpas, known for their prowess as porters and guides, name some yaks and children after the newborn’s birthday. Fura, our handler’s first name, means “Thursday.” “Kancha,” designates a family’s youngest boy. Appending the birthplace resolves any remaining confusion. The yaks bearing Nepali names were reared in Alaska, the rest shipped from Asia to Talkeetna. A calf dropped there this spring came as a surprise; the cow’s knee-long hem cloaked her pregnancy. Natives and foreigners in the off-season mix in the company owner’s pasture, and a few are herded to the uplands for these trips.

Proud, doting pastoralists worldwide adorn their cattle. Bronze bells on bright, hand-woven neckbands broadcast our yaks’ whereabouts. Swastikas on Dawa’s collar symbolize Buddha’s auspicious footprints, the karmic wheel—cosmic recycling. Young Pemba, a bull, flashes red woolen ear tassels, markers we soon learn to heed. Joseph punk-rocks a mane strand dyed orange. Hair loss exposed his neck folds, thicker-skinned than expected.

Piper has fully morphed into “Hyper” over the black, hulking shapes veiled in musk. It’s the shepherd instinct. Irked by her barking, Pemba charges, barely deflected by Dylan snapping open his hiker’s umbrella. Piper is no match for this four-legged battering ram. Tibetan wolves (and winters), however, kill bigger,

wild yaks.

I’d pay to see such forces clash.

I linger entranced by the hillside foragers. Straining to reach without stepping, they become bug-eyed. One relieving a scalp itch pulverizes a tussock. Rubbery lips and tongues uproot greenery audibly. Horns of a shortbow’s bend and span scratch pronounced humps. The grunts immortalized in this species’ Latin name counterpoint bees buzzing at flowers and wavelets lapping the shore. I recline on cushiony tundra crinkly from drought, where white, munching muzzles, swaying belly-hair skirts, and the temple-bell clanging of clappers lull my monkey mind.

By the time barbecued salmon aromas rouse me, the yaks, though not hot or mosquito-ridden, have ambled into the lake. At a later camp, one will claim a lush cottongrass island for itself. Distant relatives of the bison and water buffalo, yaks simply love to dally chest-deep in water—Tibetan toughs on a ruminative break when we put on clothing layers so our lips won’t turn blue.

Hiking

The next morning, we watch the ancient routine of beasts being burdened. Maren yee-haws them in from a bowl in the hills. Fura hitches them to climbing rope strung between a picket and rock. The odd shirker has to be dragged into position. Each hand-carved packsaddle fits a particular yak. The two feisty ones, Pemba and Jack, require Dylan or Maren to grip a horn. With horses, mostly the back-end spells trouble; with yaks, upward jerks of the anvil head. Singing to calm them, Fura fastens chest bands and cruppers to keep things from sliding. Having cinched girths and trucker-hitched balanced coolers and bulging bags in his day’s sweatiest moments, he finishes, pulling taut climbing-webbing, bracing a knee against the load. The yaks, lugging tents and heavier personal items, leave after the hikers, passing them later so camp will be ready when we arrive. Traversing alpine terrain under lightened backpacks, we like this arrangement. Eric broke his neck playing football. Rick has had both knees replaced and survived bone cancer; arthritis gnarled his hands into roots—yet he walked 600 miles on Spain’s Camino de Santiago last summer. I have lower back problems and repeatedly dislocated a shoulder.

For several hours every day, I escort the lumbering column of bovines fanning out, stopping and grabbing mouthfuls, stoking boulder physiques. Even greenhorns recognize individuals by their bodies’ cast, by fetlocks and forelocks, by demeanor, by the head-butting instruments’ bold, unique flare. Dawa, the runt, always sans baggage, always lags. Hiking-pole prods won’t rev her behind into second gear. Pemba enjoys mushrooms. He also hassles Nima who retaliates fiercely or, bursting forth, gains distance. After one bout, Pemba’s cargo needs re-tightening. The hormonal youngster never challenges Jack. That one just sitting on you would feel like burial under 200 bricks.

In creek beds, the mob vanishes into thickets, except for horn tips or the occasional hump. Mistaking one for a grizzly’s, I flinch. Galloping quickens the gamelan orchestra’s beat, but caught midline or up front, I manage to dodge these mini stampedes. Cairns form exclamation points at the route’s cruxes, bad-weather beacons reminiscent of stacks in Tibetan passes, where travelers adding stones ask for blessings or appease inscrutable, glowering gods.

Days three and four

By day three, our fair-skinned maid, wearing headphones and acting as sweep, sounds like a hoarse carnival barker. She’s a softie with animals though, which ours perceive as weakness. Fura, leading and smiling at rookie efforts, speeds up slackers by lilting their names. The marathoners in fat suits huff toward Yak Pass, tongues lolling under a withering sun. Like the Sherpas, they evolved at high altitudes. They break ice crusts to feed, chew snow when water is absent—fewer sweat cells than a cow’s conserve fluids in arid environments. A lung capacity three times that of cattle pushes more and smaller oxygen-rich red blood cells through tissues withstanding −40° temperatures. Yaks shed the dense, dark-brown winter coat underneath guard hairs to prevent overheating. Both fibers have been crafted into rugs, ropes, tents, bags, slings, fly whisks (from tail hair) and wigs, and lately, designer long johns and soundproof insulation for a Dutch museum. The donors’ surefootedness shines on the far side of Yak Pass. Graceful as Boston debutantes, they trail Fura 800 vertical feet through ball-bearings scree.

On day four, we pitch tents among choice blueberry patches after squelching in sandals through marshland and a dammed creek to aptly named Beaver Camp, six springy tundra miles downhill from Lake Camp and Flattop Mountain above whose brow a golden eagle spiraled on thermals. Throughout our descent, Denali levitated above the horizon—blindingly white, weightless, holy, attended by Hunter, by Foraker bulging yak-like—kin to Mount Kailash and Machapuchare. Ruth Glacier visibly wound from its flank, streaked black by moraine rubble from cliffs that would make El Capitan blanch.

Shaggy saints

Music from the kitchen tent—thankfully not Fura’s beloved Bollywood soundtracks—announces dinner is being prepared. Dylan, Maren, and the packer have bathed and rinsed clothes in the creek. The yaks, bedded down on our ridge near dusk, conjure bug nimbuses. In the slant light, the insects resemble crazed, gilded dust motes. Fura anoints the quietly suffering martyrs with repellent daubed onto latex gloves, out of compassion but also so they’ll stay put. They’ve fled infested sites in the past, bolting to higher or drier camps miles away. Brushing her teeth, Maren jogs circles around her bedroom before diving in as if chased by piranhas. The yaks’ peaceful chiming joins sibilants from a brook tumbling off the plateau. A waxing, Cheshire-grin moon mocks the weakening sun.

Never hobbled, the yaks normally don’t wander far. Now they crop halfway up a mountainside, now 10 yards from our tents, homing in, as a rule clustered, on the richest green. The term “herd mentality” is unflattering, really; safety can be found in numbers, together with warmth, comfort, and room for distinctiveness.

Willows, dwarf birches, cow parsnip, and alders choke the stretch between Beaver Camp and our pick-up location. Scattered spruces appear, each adult tree rust-brown, an upright, beetle-killed corpse forecasting the apocalypse. Over the years, the yaks have dozed trails through the vegetation, wider, more entrenched than caribou paths. Still, we get bunched up behind them because they’re flagging in untimely heat.

Moon Shadow Lake blues a basin ringed by knolls. Bearberry leaves have begun their blushing and fireweed the loosing of silky seed fluff. I take a bracing swim, beholding Flattop Mountain hazy with distance. Tomorrow, the wranglers will hike the yaks out, an overnight trip. Fura lifts his last can of “fish beer” in celebration, his cherished Sockeye Red, which Eric praises too. The taciturn Nepali then cleaves a skewer from a birch log with his khukuri, the crooked multipurpose blade. It’s steak night. Should Dawa worry?

As the first floatplane, shattering stillness, alights the next day, I bid farewell. My silent namaste salutes fellow incarnations: dreadlocked Buddhas, shaggy saints, patient, beautiful souls.

Comments are closed.