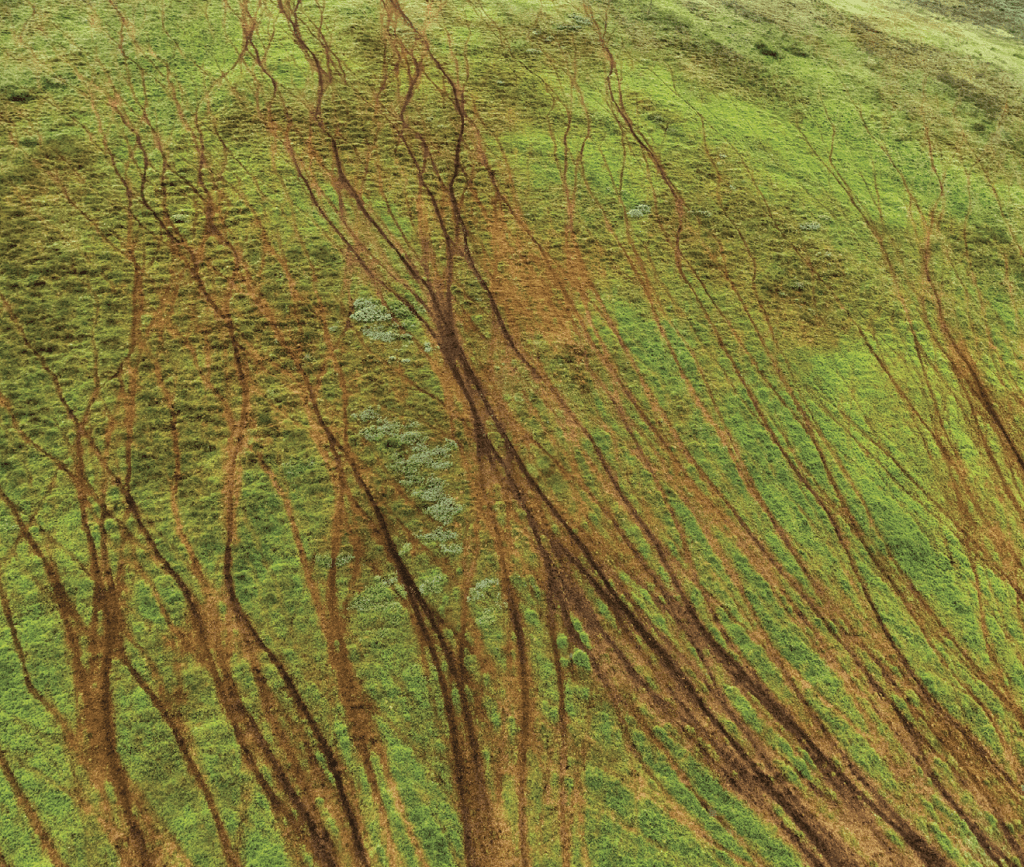

Above: What from an airplane perspective resembled a hostile rucked labyrinth. Courtesy Lisa Hupp, USFWS

Note: This excerpt from Michael Engelhard’s new memoir, Arctic Traverse: A Thousand-Mile Summer of Trekking the Brooks Range, (Mountaineers Books) is printed with permission.

Day 5 of 58

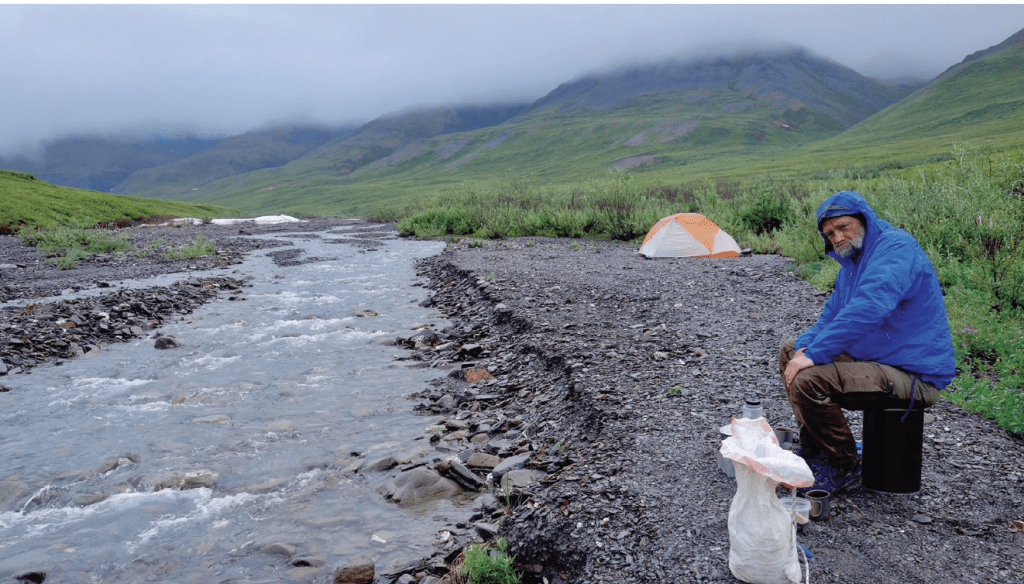

Map: Table Mountain

Barely a day passes without some graphic reminder of mortality, whether close bear encounters or bones scattered on the tundra—a skull, scapula, vertebrae, or mummified leg with hoof attached. On a gray morning, while I cross aufeis—a carapace of last winter’s river ice—strangely radiant, as if it were collecting what little light there remains, a shred of blue above and ahead feels ethereal, like a window onto the afterlife. Unlike on other outings, I have blebs not on my feet, which stay wet more often than not, but on my hands, from my tussock crutches. My hands are soft, a milquetoast writer’s, not callused as usual at this time of year from days at the oars already.

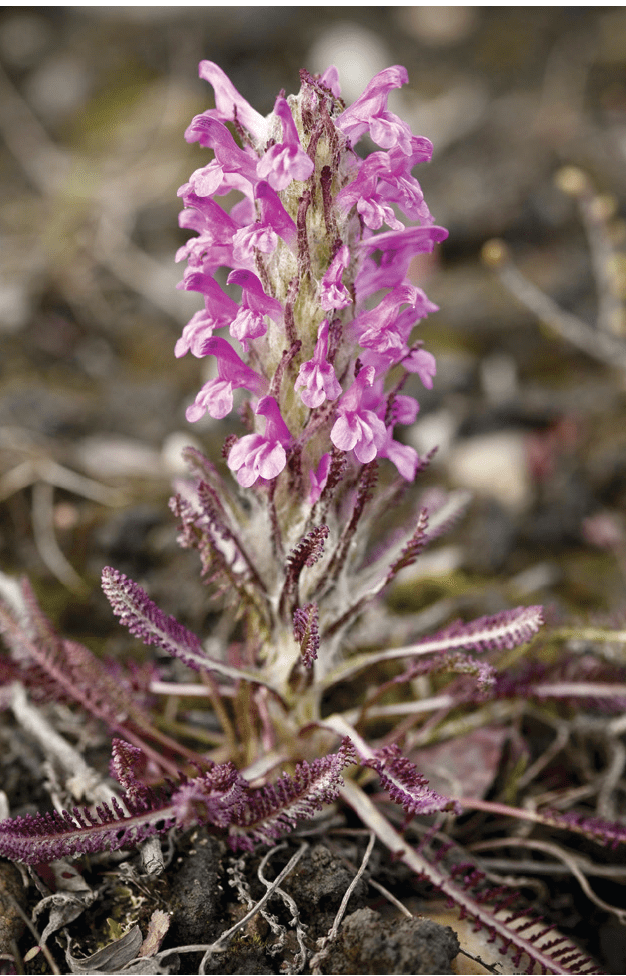

Woolly louseworts in bloom evoke strawberry ice-cream cones. It is too early in the trip for such cravings.

I reach the Kongakut near its elbow, the first familiar landmark since Joe Creek, near the Canada border. Memories flood in, of Drain Creek, Whale Mountain, Icy Reef. River trips launch in this vicinity, and I did on my first arctic float as a rafting guide. An Australian couple in a basecamp I pitched at Caribou Pass donated a thermal underwear top and bottom, as I’d been woefully unprepared for a cold front sliding in from the Arctic Ocean. I really needed it on the following hike to the coast with a different pair of people, along the Clarence River to Demarcation Bay. My hikers had vowed they would take a dip once we got there, for bragging rights. After testing the water with a finger, they’d changed their minds. They always do.

The Kongakut, easternmost of Alaska’s popular North Slope rivers, throws gnarly rapids at boaters. The biggest one killed two Californian women paddlers on a guided trip. When disaster strikes wilderness enthusiasts, I often hear, “At least they died doing what they loved doing,” as if that were consolation. Taking their last breath, pale with terror, blue with regret, the doomed may have hated what they were doing. They certainly would have preferred to keep doing just about anything.

A different, less hairy beast on its milder stretches, “the Kong” boasts good fishing holes, sail-finned graylings, and five-pound arctic chars.

What is this need to abbreviate? “The Kong,” “the Hula” (Hulahula) . . . more than three syllables seem a bother. Some writers refer to “the Brooks,” omitting the most important part: the range. We also clip syllables elsewhere: “Flag” for Flagstaff, “Frisco” for San Francisco. My wife says frequent flyers pronounce abbreviations on luggage tags instead of their destination’s name. Hence, “AKP” for Anaktuvuk Pass, “NUI” for Nuiqsut, “KOTZ” for Kotzebue. Otto von, the old Baltic globe circumnavigator serving Tsar Alexander I, would have been indignant. Named after him, the Bering Sea burg is the intended terminus of my traverse, bookend to Joe Creek and forty-five jet minutes from Nome, so I have a certain fondness for it. The casual language, I suppose, projects familiarity with the subject, distinguishing speakers as insiders, whether or not they have earned that status.

I’m easily entertained, admittedly, and out here, aside from the antics of wildlife, have to find amusement in myself.

From the heights, I see a huge aufeis field and large inky stretches of open Kongakut. Willow flats sprawl where the current changed channels and unburdened itself of trainloads of gravel. Dwarf birch covers the bluffs I walk without undue effort toward my crossing.

Vegetation in part determined the course of this traverse. Forest and thickets of alder and willow, despite spilling over the Brooks Range where they infiltrate sheltering draws, foremost cling to its southern slopes. Global heating’s greening of the Arctic is changing that fast. Still, I chose a southerly route. At this time of year, south-facing passes and slopes should largely be free of snow, in theory. This, however, puts me in brush more often than a walk on the coastal side of the divide would. Having traveled the middle and lower reaches of the region’s major north-south trending rivers during my ethnographic fieldwork and on private trips and those I have guided, I know I must cross as near to their sources as possible to avoid the deep, raging currents June snowmelt feeds into them.

I did not bring a floatation device for crossings so will have to make all of them by wading. Though a few valleys run east to west, the majority of my planned route goes against the landscape’s grain, requiring that I scale dozens of passes. I will loosely stick to the Continental Divide here in the Rockies’ northern tail. In these parts, the great watershed separates the Beaufort Sea from the Chukchi Sea drainages; its dot-and-dash line doglegs from north to south into east to west, yet another trick of plate tectonics, and I shall vault it repeatedly.

Thumps of aufeis shelves collapsing into the Kongakut herald summer. Boaters in early June scout the moribund ice because streams sapping it sometimes flow underneath. In 2003, a father and son on the North Fork of the Koyukuk in Gates of the Arctic got stranded for four days in T-shirts and with one pair of boots when their raft hit an aufeis shelf, tossing them into the drink. The current dragged them under it for a hundred yards before spitting them out at the far end. An air pocket where they briefly clung to the ceiling saved them from drowning, but they got scraped up badly and lost everything but one lighter. Cautious guides on early-season river trips carry ice screws and lines to quickly anchor their boat to a wall should they round a bend only to face a cold, dark maw.

I think of Edward Abbey, a writing influence early in my career. For him, who never much liked Alaska, it was “our biggest, buggiest, boggiest state.” At that stage in his life, he wrote on assignment for glossy men’s magazines, all expenses paid, a far cry from the desert dirtbag of pre-Desert Solitaire days. The curmudgeonly writer felt out of his element here, and professional guides led both of his Alaska excursions.

Despite his yearning to experience nature at its wildest and woolliest, Abbey never saw a brown bear, not even at the Tucson zoo, where one hid in its den on the day he visited. His friend “Grizzly Man” Doug Peacock, the model for Hayduke in Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang, carried an eight-foot homemade Inuit-style spear once as a security guard on a Canadian arctic expedition. Even Peacock could not get the familiar Montana bears to show themselves to his pal Ed.

Debbie Miller, an author and former Arctic Village teacher who lunched, fished, and birded with Jimmy Carter and his wife Rosalynn during their stay in the refuge, also met Abbey, in Kaktovik. “He had just floated the Kongakut River,” she recalls, and “perhaps what surprised him most was an American robin that perched near his tent, singing its joyful song in an arctic gale.” The robin, which Abbey knew from his Tucson backyard, impressed him as living evidence of an epic unrest. Like all migrants, it combines here and there in one body. Yet in his essay about the adventure, the man receptive to nature described Barter Island, the home of three hundred Inupiat, as “the most dismal, desperate, degraded rathole in the world.” On a clear fall day, the Brooks Range scrimshaws Kaktovik’s southern horizon—snowy, majestic, above a powder-blue piedmont. The embittered writer coming down with the flu called the bear “the hypothetical grizzly.” “I have seen but little of the real North,” he confessed at the end of “Gather at the River,” “and of that little understood less.”

Upon reinspection, hero bronzes on pedestals sometimes have clay feet. Sledgehammer them so you can stand eye to eye.

More birds enliven the Kongakut than anywhere else on my route thus far: gulls, loons, ducks, tree and white-crowned sparrows, and jaegers—buoyant, yelping gulls with hooked bills and tails one could take for long stingers. Unlike ravens, white-crowns speak differing tongues. Bird repertoires stay fixed neither geographically nor historically. Singing cultures like the white-crowns innovate. Males conspicuous on the highest branches stake claims and announce their mate qualities in dialect. Musical cliques inhabiting segmented landscapes may evolve into new species. Sonograms allow visual and computer comparisons of their vocal styles, and those of other singers, thereby revealing population sizes, their relatedness, and environmental shifts.

Before the trip’s end, my notes in the map margins will spill over onto the backs of six four-square-foot map sheets, cluttering them with the tiny, curlicued extracts of my days. I realize how much richer the hours have been here than in town, how much life can be packed into mere minutes. My attention is keener, less scattered, yet paradoxically wider, more open than in the humdrum boxes of urban routines.

My script crowds expanses on the maps as the waypoints of explorers once did, possibilities turned into facts, at least, if not certainties. The small tent-shape triangles with which I mark campsites align into a string of prayer beads that shield me from a harsh world. Each one signifies a sweet home away from home. Writing and travel in their linearity and directedness overlap. The first sentence to put on a page can petrify you; so can first steps into the unknown, and you don’t know where either will lead. Places fantasized about before with the help of these maps now cohere. First, they become reality, and too soon will exist for me only as memories. What from an airplane perspective resembled a hostile rucked labyrinth has started to feel like boots broken in well.

The author trained as an anthropologist and worked for 25 years as a wilderness guide in the Canyon Country and Alaska. Learn more at michaelengelhard.com.

Comments are closed.