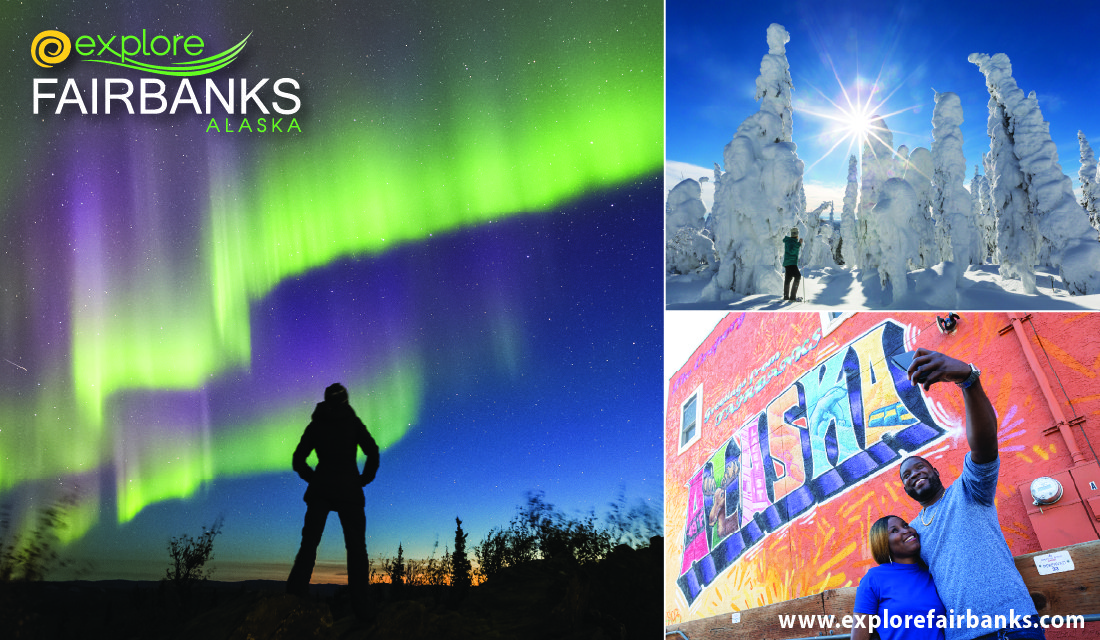

A bull moose gazes at the photographer in this shot taken during the autumn rut in Alaska’s Kincaid Park. Photo by Ken Marsh.

If your mind isn’t clouded by unnecessary things, this is the best season of your life. ~ Wumen Huikai

Alaskans hunt and gather because it is our tradition and because the land is willing; even when times seem hard, say, in darkest, cold December, Alaska has a way of providing for her own. Yet of the seasons, none better define this culture of living off the country than the golden days of late August through October. Not even summer provides for its denizens more broadly or more certainly than do the days of fall.

Particularly if you look beyond the belly and into the soul.

A couple of Septembers ago, I went about my lifelong moose hunting ways, but with a camera instead of the old Remington 30.06. Near a thicket of flaming-yellow devil’s club—thorny, waist-high shrubs with foliage resembling giant, spine-spiked maple leaves—I’d spotted a large bull with a harem of cows. The early morning was frosty, the sun barely touching the cottonwood tops. Steam puffed from the bull’s nostrils as he jealously nuzzled his ladies.

Distracted by the autumn rut, bull moose often discard their fear of humans. With hormone-swollen necks and menacing antlers, they strut dangerously through Alaska’s wildest corners and biggest cities alike, searching for cows—and for trouble, in the form of other bulls or anything else alive or inanimate they might perceive as a challenge, including mailboxes and railroad engines.

Alaska’s fall colors reach their zenith this time of year, much to the delight of photographers who travel to far-flung locations like Denali National Park to capture dramatic images of bull moose locking antlers against the taiga’s brilliant scarlets and golds. Over the last decade or so, large autumn concentrations of moose have been discovered much closer to the mainstream, on the outskirts of Alaska’s largest metropolis. Glen Alps, a gateway to Chugach State Park in the mountains backing Anchorage, now draws throngs of wildlife photographers and viewers each September and October as moose gather in exquisite high-country settings.

Kincaid Park in South Anchorage—a five-minute drive from Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport—also offers superb moose viewing. The heavily wooded park is traversed by trails traveled by mountain bikers, hikers and, in winter, cross-country skiers. The trails are used by moose, too, and encounters there are frequently up-close; wildlife viewers and photographers are advised to employ due caution.

On that cold morning two Septembers ago, I watched my photo opportunity unfold: Framed by the forest’s fall colors, the bull tilted his heavy rack as he moved from cow to cow, grunting, pink tongue lolling. The cows, with dark eyes and frosty-gray coats, glided through the brush like ghosts. All the elements were there. To capture some fine, frame-filling images, I needed only stalk a bit closer.

Moving when it seemed no eyes were upon me, I advanced a few feet at a time, stopping at intervals to plant my tripod and snap a shot or two. The cows seemed to ignore me completely, but now and then the bull would halt and glare suspiciously in my direction. At one point, a twig snapped behind me and I wheeled to discover a curious cow moose had sidled in to study me at arm’s length.

For a moment, my heart pounded.

With little alternative, I stood my ground and the close-up cow, apparently deciding I presented no imminent danger, ambled away.

The bull, meanwhile, had turned his attention to another cow, and I felt secure enough to resume taking pictures. From my viewfinder, I watched as the bull eased up to the cow and began nuzzling her flanks. The old boy had ideas, but the cow was having none of it. She bolted, leaving the rebuffed lothario standing alone and, apparently, humiliated.

In hindsight, I should have shown proper respect and stopped shooting, because when the bull heard a final “click” from my shutter release he jerked his head in my direction and focused his bloodshot eyes hard on me. I felt like I’d been marked as the third party in a soured love triangle.

Jealous and full of spite, the bull charged.

In that instant, the world faded into a yellow-and-red September-themed blur punctuated by an angry, oncoming, 1,600-pound bull moose. Nothing else existed—except for a nearby spruce that seemed to call out — not even the $3,000 worth of camera gear I left deserted on my tripod.

I had no time to climb the tree. Head down with snot flying from his nostrils, the bull was on me in a heartbeat. I dived through the low-hanging branches and placed the trunk between me and the bull. The bull chased me around one side of the trunk, then turned and pursued me around the other. Then he stopped and, snorting and grunting, began thrashing the tree—trunk, branches, and all—with those antlers nearly six feet wide and four feet tall. I dodged as foot-long tines pierced the air inches from my face.

Something inside me seemed about to explode when, abruptly, the bull stopped, those murderous tines still inches away. I froze, afraid even to breathe. Then, as if our score were now settled, the bull lifted his head and stalked off toward the cows, never looking back.

Even in its calmer moments, autumn in Alaska imparts a sense of exhilaration—a feeling of sliding out of control down a sheer, rough slope. A round with a raging bull moose highlights that. It will also clear your mind.

As I gathered my gear and left on shaking legs, I breathed in the sweet-and-sour fragrance of currants and high-bush cranberries. The air felt sharply cool and the fall colors around me seemed more vibrant than ever. I was swept at that moment by a tide of joy, and by the realization that I was indeed living the best season of my life.