“How many trees do you think there are in Canada?” It was another one of those unanswerable road trip questions. Pat glanced sideways at me from his place behind the steering wheel. “I’ll Google it,” I said, turning to what has become our go-to source for entertainment on long, lonely stretches that give us time to ponder such inanities. In this case, we were somewhere on the Alaska Highway in British Columbia heading north, driving his camper back home.

As I searched on my phone (there are a surprising number of cell towers sticking up out of the miles and miles of forest along the way), Pat tossed out a guess: “Five hundred billion.”

“Close,” I said. “Almost 318 billion.” Our conversation tunneled into the minutiae of how the number of trees in a country is even estimated. Having a captive audience and time to spend conversing in person is one advantage to such long road trips. Another is simply appreciating the vast and varied northern landscape.

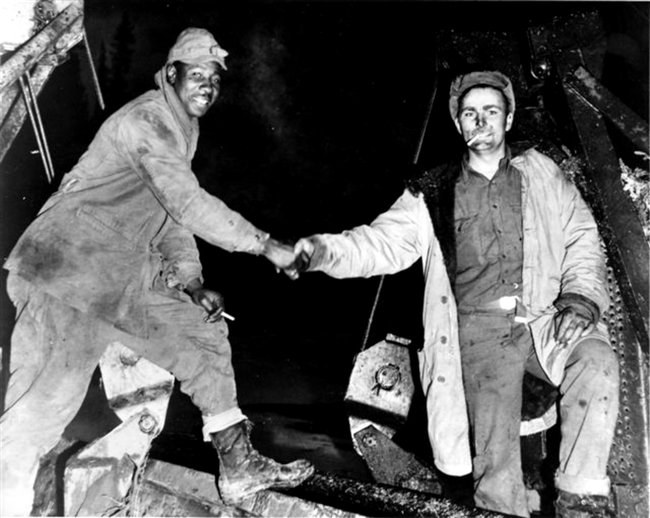

Officially called the Alaska Highway but still referred to as the “Alcan” (short for Alaska-Canada), the thoroughfare turns 80 this year. The idea for a road connecting the contiguous United States to its northernmost kin originated in the 1920s, and the project finally coalesced during WWII as a supply track. The Alaska Highway was completed in 1942. It begins at mile 0 in Dawson Creek, British Columbia, and runs to mile 1387 at Delta Junction, Alaska. Various access routes from the Lower 48 arrive at or near Dawson Creek. We took the Canadian Rockies Route, crossing the border at Kingsgate Canada station (north of Coeur d’Alene, Idaho), then heading through Banff and Jasper (where we saw, within minutes of entering the first national park, a black bear just feet from our lane, and eleven minutes later, a grizzly grazing on roadside grass). From there, we drove west to Prince George, then north on the West Access Route to near the beginning of the Alaska Highway. While it would be impossible to list every must-see along the way, below are a few of my favorites (Alaska Highway miles shown are from Dawson Creek).

BRITISH COLUMBIA

1) Hudson’s Hope

Hudson’s Hope Loop

Not technically on the Alaska Highway, this hamlet is so close to Dawson Creek and is such a lovely stop that it’s a worthy jumping-off point for our purposes. As the afternoon sun crept toward the horizon on our second day in Canada, I perused our MILEPOST® for a suitable campground. For us, that always means as quiet as possible.

“Listen to this one.” I read aloud: “Alwin Holland Memorial Park (half a mile off the highway) is named for the first teacher in Hudson’s Hope, who willed his property, known locally as The Glen, to be used as a public park.” The guide listed just a handful of sites. We pulled in, and other than an empty car in the day-use area next to a trail leading down to the Peace River, we were the only occupants.

Once settled, we carried camp chairs and a beer each to a scenic rocky ledge overlooking the river. Nesting Canada geese honked atop a huge outcrop mid-channel, and we watched the sun slowly set on the, indeed, peacefully flowing river.

The region is known for dinosaur tracks and fossils. Its hydroelectric system employs much of the community. Like much of North American history, tales of the town include the ups and downs of indigenous/colonial relationships, trade and transportation, and use of natural resources. Hudson’s Hope today is billed as the “playground of the Peace” for its outdoor recreation opportunities.

2) Tetsa River Services and Campground

Mile 357.5

When I saw in The MILEPOST® that this business bills itself as the “Cinnamon Bun Center of the Galactic Cluster,” I knew we had to stop and sample one. And one was all they had left by late morning. As I haven’t yet traveled the entire galactic cluster, I can’t vouch for their claim, but we did scarf the sweet, warm, buttery pastry like starving wolves, so…I wouldn’t doubt it.

3) Muncho Lake

Mile 437.3

Cradled in mountains that rise to more than 6,600 feet, Muncho Lake is part of a provincial park and allows camping in designated campgrounds. A picnic stop along its shore is a great way to appreciate its turquoise tint, attributed to the copper oxide that leaches from the bedrock below. Overnighters looking for cushier accommodations than a tent or RV afford can get a lakeside room at the pet-friendly Northern Rockies Lodge and enjoy a meal in the establishment’s restaurant and lounge.

Since we were only passing through, we parked at the boat launch and stretched our legs in the midday sun while we munched at Muncho. The name, however, has nothing to do with noshing, but rather means “big lake” in the local indigenous language. In fact, at 7.5 miles long, it is one of the largest natural lakes in the Canadian Rockies.

4) Liard River Hot Springs

Mile 477.7

Since water seems to be a theme in my preferred B.C. highlights, I’ll stick with that for one last recommendation before leaving the civilized south for the wild north.

Among Alcan veterans, one must merely say the word… Liard …to witness its effect: Eyes widen and roll, lips part, an emphatic “Ooh, Liard!” escapes the besotted. It’s that good. Bathers walk to the spring’s natural setting via a short boardwalk trail over wetlands that support dozens of boreal forest plants, including 14 orchid species. Native vegetation rings the pool. Facilities include a changing house and composting toilet as well as a large deck with multiple sets of stairs leading into the steaming, barely tamed outdoor spa. Enter slowly, for temperatures range from 107 to 125 degrees Fahrenheit.

I have been to Liard in both winter and summer and have even considered driving all the way there from my cozy Alaskan abode (1,061 miles—I checked Google maps) for a few days just to partake in the gold standard by which all others are measured.

5) Wildlife Sightings

Black bears and grizzlies, stone sheep and bison. If you drive the Alaska Highway and don’t see at least one of these species, you probably should make an appointment with the eye doc (and hand over the keys). Occasional lynx, fox, caribou, and elk sightings are possible too.

Small herds of wood bison lumber at their own pace beside—and sometimes across—the Alaska Highway near the B.C.-Yukon border. Watch for these bulky bruisers and their frisky calves during the summer; if that’s not in the cards, you’ll surely see their wallows left behind—car-size divots in the dust.

Stone sheep also like to hover around roadways. They are a subspecies of thinhorn sheep, so called because their horns are smaller and thinner than bighorn sheep that range farther south. The other subspecies of thinhorns are Dall sheep, an all-white version and Alaska’s only wild sheep. Stone sheep, sporting dark hair (sometimes with a punk-rock flair on the nape of their thick neck), and a white rump and head, are named after Andrew J. Stone, a hunter/explorer active at the turn of the 20th century.

Grizzlies, forever the money shot of wildlife sightings, might present themselves near the pavement for your viewing enjoyment—or just because they can. The closest one we saw was parked conveniently across from a large pull-out. We U-turned as quickly as one dares in a seven-ton truck and camper combo and approached the bruin ever so slowly, stopping six feet from it, diesel idling. I pressed the window control button for the briefest of seconds, enough to allow a clear view for my camera, raised and pointed at the buff (in color and fitness) beast. Pat’s dog, Bella, barked and whined and scrabbled at a plastic tub of things in her way on the back seat in an attempt to show that bear who was tougher. I filmed the encounter while also trying to really look at the bear instead of just the digital display, aware that one lunge could land the griz at my cracked-open window. “Be ready to gun it,” I either thought or said. Pat and I whispered, never taking our eyes off the prize. Buffy chomped away at happy yellow dandelions, chocolate-colored paws planted squarely, elbows out, swinging its gigantic head from side to side and looking around as it chewed with its mouth open. It never even gave us a glance.

Black bears? Meh. I stopped taking photos after about the 20th one we saw. The cubs are extremely cute, though, and seriously, you will see black bears while driving the highway.

YUKON

6) Whitehorse

Mile 887.4

My memories of Whitehorse run the gamut. With my parents in the 1990s, I camped and soaked at Takhini Hot Springs, now a brand-new facility called Eclipse Nordic Hot Springs that sports multiple soaking pools fashioned in a Japanese style. With friend and fellow writer Susan Dunsmore in 2018, we visited friends and launched a double sea kayak into the Yukon River from Rotary Park on day one of the Yukon River Quest race. I’ve stopped there briefly to refuel and restock.

Whitehorse is the capital of Yukon and makes a great base or jumping off point for adventure. This city of about 30,000 people offers all the usual travel amenities plus museums, art galleries, and outdoor recreation opportunities. Other routes besides the Alaska Highway lead from Whitehorse toward Dawson City, Skagway, and into pristine mountain ranges.

Alaskans have long loved driving the loop from our state to Dawson City, center of the Klondike Gold Rush and home of a very interesting riverboat graveyard, then Whitehorse and back. It’s a perfect multi-day adventure for anyone who enjoys being surrounded by wilderness but doesn’t want to be too far from civilization.

7) Village Bakery and Deli in Haines Junction

Mile 985

Even if you’re not that hungry when you stop at the Village Bakery and Deli in Haines Junction, you’ll leave grasping brown paper bags of goodies and even more sacks cradled in your arms. This shop brings a whole new meaning to road snacks. You’ll probably even stash entire meals in your camper or RV fridge. This treasure trove of deliciousness, including gluten-free, dairy-free, vegetarian, and vegan options, can break the bank—not because their prices are high, but because you’ll be tempted to say, “I’d like one of everything, please.”

Pretty much everything is what they sell: fancy dessert bars, pie, cake, brownies, cookies, loaves of bread, pizza, soup, muffins, scones, salad, quiche, meatloaf, lasagna…the list goes on. And like any good eatery, it has good espresso and organic teas plus other drinks like lemonade made from scratch.

This small-town jewel has been open every summer since 1989.

8) Side Trip to Haines

Haines Highway

A mere 146 miles south of Haines Junction lies the community of Haines, home to Heather Lende, the current Alaska State Writer Laureate; Alaska magazine’s own Nick Jans, seasonally; a bald eagle preserve that our senior editor, Michelle Theall, visits each winter to lead photo tours; historical landmarks; a state ferry terminal; and much more of note. The next time I visit, these are on my list of must-sees and must-dos: Sheldon Museum & Cultural Center, Kroschel Wildlife Center, hike Mount Ripinsky Trail, and imbibe at the Port Chilkoot Distillery (Seaworthy Rum or Wrack Line Rye, anyone?).

9) Kluane Lake

Mile 1020 to about 1070

Yes, Kluane Lake is that long—officially 50 miles but shrinking as, in 2016, its main water source, the Slims River, suddenly disappeared. Meltwater from Kaskawulsh Glacier had, for 300 years prior, fed the river, but the glacier began to retreat in the 1950s, and accelerated climate warming between 2007 and 2016 forged new drainage channels that changed the bulk of the flow from north into Kluane Lake (and eventually the Bering Sea) to south into the Kaskawulsh River (and eventually the Gulf of Alaska). Billowing dust clouds now frequently envelop the Alaska Highway where it crosses the dry inlet.

Kluane’s surface level may slowly decrease, but for now, it’s still a massive, raw body of water to behold—the largest lake, in fact, situated entirely in Yukon. Two small communities, Burwash Landing and Destruction Bay, are located on its western shore. My favorite way to experience Kluane is to camp near it or walk the beach. Winds strong enough to lift small pets off the ground are common. Years ago, my mom and I stayed at what is today the Congdon Creek Campground but had to spend the entire time inside the tent due to gusts that nearly knocked us over when walking. We played word games while the fabric ballooned and clapped around our heads. Tenters these days are only allowed to stay inside an area cordoned off with electric fence due to the prevalence of roaming grizzlies.

On my most recent visit, Pat and I leaned into the whipping wind as Bella, big enough to hold her own against the gale, laced her way through the brushy edge between campsites and beach. Whitecaps appeared and disappeared, and shoreside ice bobbed and tinkled in vigorous waves.

ALASKA

10) Choices Near Tok

Once past the border, the highway continues northwest, and those of us coming home to Alaska reliably declare, “Home stretch!” as we cruise along the edge of the Tetlin National Wildlife Refuge, see the Wrangell Mountains to the south, and begin to glimpse the eastern end of the Alaska Range. But road trips get under your skin, and sometimes a person needs another few days for “reentry.” Despite the comfort of familiar landscapes, travel momentum sometimes carries you home via circuitous routes.

At Tetlin Junction, mile 1267, the Taylor Highway turns north toward the towns of Chicken and Eagle and links to the Top of the World Highway, which leads east to Dawson City on the far side of the Yukon River. It’s part of the loop I mentioned in the Whitehorse section.

At Tok, mile 1279, the Tok Cutoff leads southwest to the Richardson and Glenn highways, which in turn afford travelers the choice to head to southcentral or interior Alaska. From Tok, the Alaska Highway continues another 108 miles to its terminus at Delta Junction. From there, Fairbanks beckons.

Poor Pat. He’d already been living out of the camper for more than two months in the southwest U.S. by the time I flew down to drive it back with him. Had I not enthusiastically suggested we “stop by” Chena Hot Springs in Fairbanks “on the way home,” he surely would’ve turned left at Tok and stepped on it like a horse for the barn. But he humored me, and we continued to the end of the Alaska Highway and beyond.

Comments are closed.