It’s 1957, and things are different. Anchorage, Alaska, is but a whisper of its future self. Oil has yet to be discovered beneath the permafrost of the North Slope, there are more gravel roads crisscrossing the city than there are paved, and the city’s population (a mere 40,000) is abuzz with a palpable fear: impending nuclear war.

Above the city at 4,000 feet, Mount Gordon Lyon rests stoically as 60 vertical feet of its peak are blasted away by dynamite.

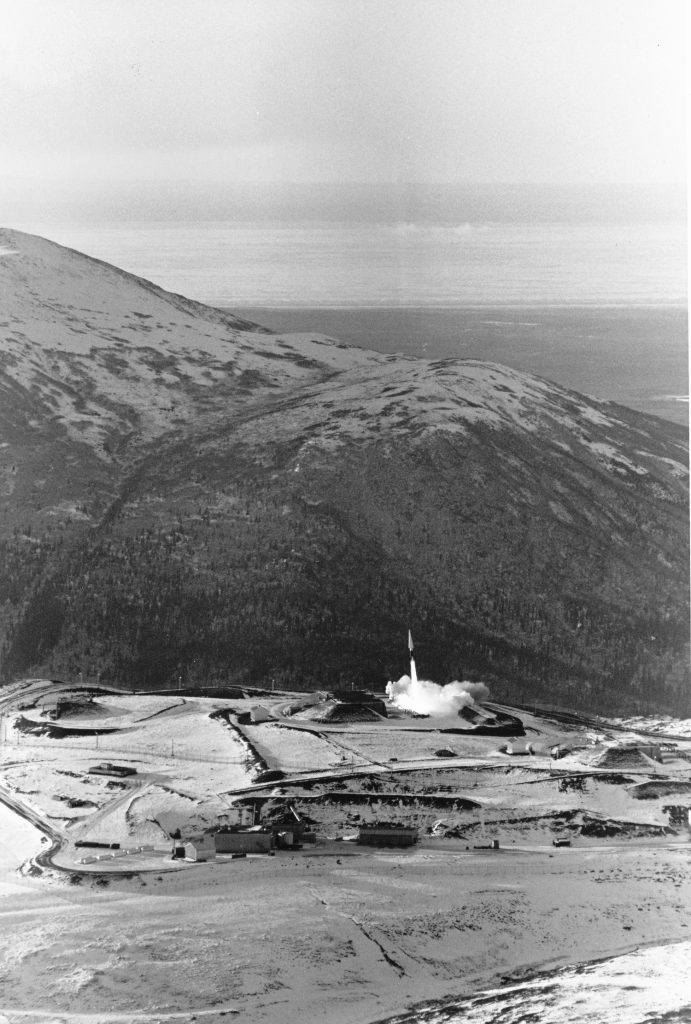

Two years later, Gordon Lyon’s now-level summit is unlike any other in the surrounding Chugach Range. Its surface, officially dubbed Site Summit, is studded by a platoon of buildings, while a silent company of Nike Hercules surface-to-air missiles, all 41 feet tall, lean skyward on its south face. The site is manned by 125 soldiers, operates 24/7, and is guarded by a rabble of hundred-pound German shepherds. If the Soviet Union, just a stone’s throw away to the west, decides to launch a nuclear attack on the United States, the Hercules missiles will surge 100,000 feet into the atmosphere and detonate their 20-kiloton nuclear warheads. The Soviet bomber planes wouldn’t be vaporized as you’d expect—they’d be flying well below the weapons’ trajectory—but they would be utterly disarmed courtesy of the electromagnetic pulse generated from the nuke’s blast. “Close only counts,” says Site Summit veteran Greg Durocher, “in horseshoes, hand grenades, and nuclear warfare.” The good news is that none of these rockets were ever launched, at least beyond test firings, and even these had to end in July 1964 due to population growth in Anchorage.

I’m sitting in a coffee shop, perhaps 13 miles from Nike Site Summit and over four decades from when it was still in operation. Greg Durocher sits across from me, relaying stories from his tenure at the site from 1974 to 1976. Cold War action, at least concerning the Hercules missiles, had slowed by that point, and a typical day at Site Summit involved manning the sentry stations, training the attack dogs, and pacing the boundary fences while trying not to “die of boredom.”

Rapid changes in the international political climate, as well as the development of intercontinental missiles, had brought Site Summit (and all 145 Nike sites scattered across the nation) to a point of near-obsoletion in 1965. The majority of these missile sites were phased out and left in various stages of abandonment, while all Nike Hercules systems were officially deactivated in 1975. Site Summit remained one of just two sites still in operation until 1979, when it was finally put on stand-down status by the U.S Army. It was officially abandoned in 1986.

It seems as though this would’ve been the end of Site Summit’s story—and it nearly was. Mt. Gordon Lyon’s unforgiving weather left many of the site’s components either disintegrated, dilapidated, or totally destroyed. Thieves and vandals followed suit. 1989 saw the end of the Cold War, and though this spurred many to try and preserve Site Summit as one of the era’s most intact missile bases, all early efforts failed. It wasn’t until 1996 that the site was officially listed on the National Register of Historic Places, though by the early 2000s the military had entered into discussions about demolishing the site.

Luckily, in 2007, a group of concerned Anchorage residents organized the Friends of Nike Site Summit (FONSS) as a statewide committee to the Alaska Association for Historic Preservation. FONSS asserted that Nike Site Summit was one-of-a-kind; the best example of a Hercules missile site and a living tribute to all of the men and women that stood by to defend our country amidst the tensions of the Cold War. It needed to be preserved. FONSS was successful in its mission and, in 2010, began work on restoring the site, as well as guiding tours led by site veterans like Greg Durocher (now FONSS director). Like any true restoration project, the work is never-ending. To see this piece of Alaskan history for yourself, arrange to take a tour in the summer months by visiting nikesitesummit.net.

By now it’s 2022, and things are different.

Anchorage is a fully-fledged metropolis, home to 300,000 people and thousands of streets, most of them paved. Oil flows from the North Slope to the majority of our pockets every year, and we’re not worried about the possibility of nuclear Armageddon (at least not most of us).

It would seem that memories of Nike Site Summit—of the Cold War itself and all of the paranoia that hung in the air like ground-fog—have faded into the rearview, and new generations that never lived through it might look at you funny if you mention it. But the fact is, from Thanksgiving weekend until March of every year, all of Anchorage is reminded every time the sun goes down. All it takes is a glance to the northeast, where the stage of Chugach Mountains towers like battlements, where Mt. Gordon Lyon once had its top blown off by dynamite, and where an irregular shape now glimmers like the brightest constellation you’ve ever seen: a star. The Christmas Star, as it is locally known, was constructed at Nike Site Summit in 1958 as a gift from its soldiers to the city of Anchorage. Once just 15-feet wide (and barely a pinprick when viewed from downtown), the star is now 300 feet wide and remains lit throughout the Alaskan winter, as well as annually on September 11th. The Star serves as a monument to a bygone era; a testament to the strength we’ve mustered as Americans, and to the people that guarded our country those many years ago.

Comments are closed.