A Family Endeavor The source of the garnets is an above-ground mine located approximately seven miles from Wrangell near the mouth of the Stikine River at a place aptly named “Garnet Ledge.” Garnets are crystalline gemstones formed under great heat and pressure that are translucent and red. At this location, they are embedded in a bedrock layer made up of very hard schist. The first documented commercial use of this site dates back to 1907 when two sisters formed the Alaska Garnet Mining and Manufacturing Company, reportedly the first all-female owned corporation in the U.S. This endeavor did not use the garnets as gemstones, but rather made them into sandpaper, which they produced into the 1930s. Ownership of the site changed hands several times over the years, and in 1962 it was bequeathed to the Boy Scouts of America from then owner, Fred Hanford. A stipulation that he included in…

Alaskan cruising is booming. Last summer, a record 1.6 million people took a cruise to Alaska, mostly aboard very large ships carrying thousands of passengers. But you don’t have to cruise Alaska that way.

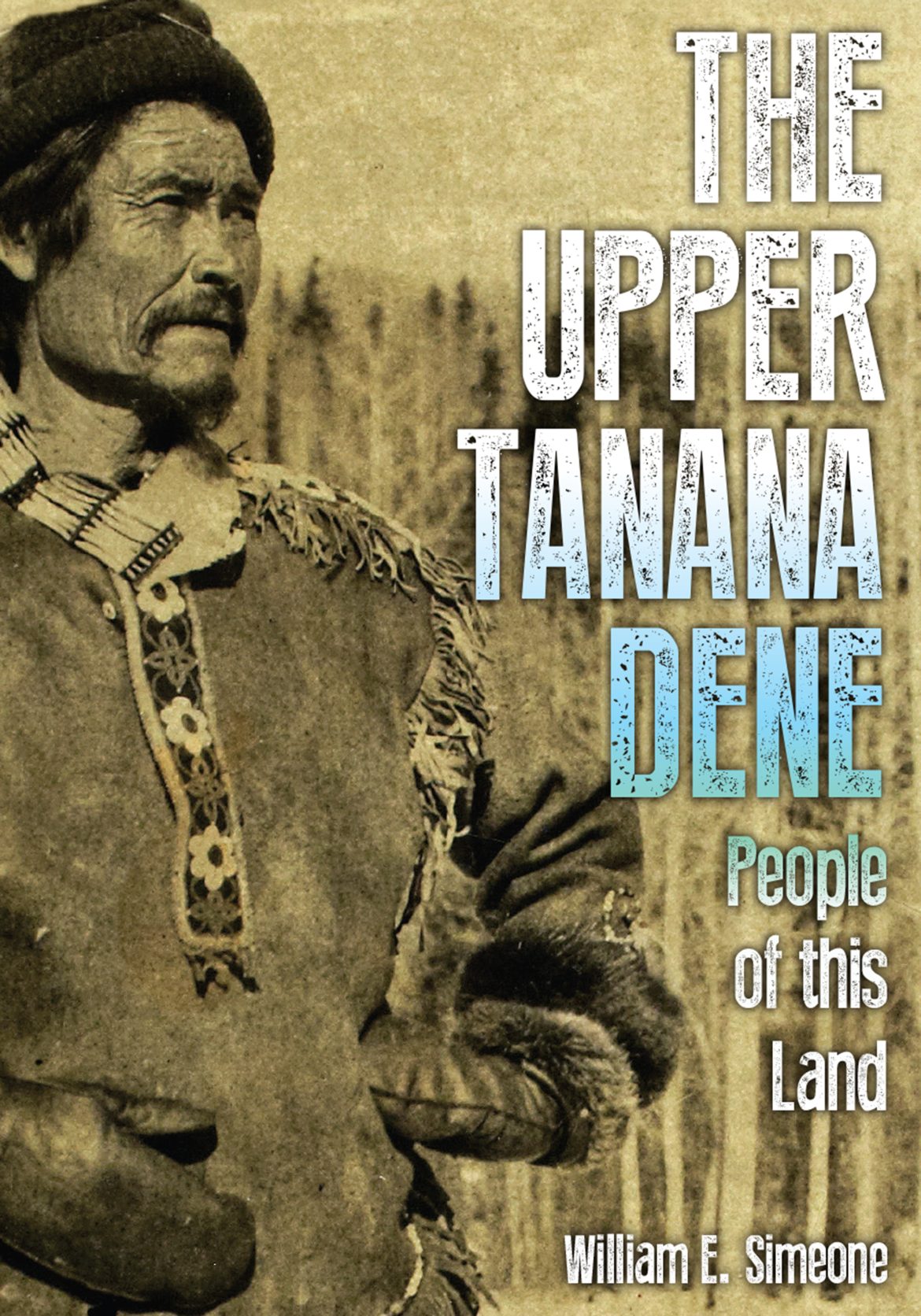

Oral history on the upper Tanana Dene released The Upper Tanana Dene, People of this Land (University of Alaska Press), offers a portrait of an Alaska Native people both before and during the transformative changes of the 20th century. It centers around oral accounts from Dene elders born in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Additional historical and anthropological information provides context. The upper Tanana region of eastern Alaska is bordered on the south by the Wrangell Mountains and on the north by the rolling Yukon-Tanana uplands. It’s a boreal forest landscape with broad river valleys, expansive wetlands, and abundant fish and wildlife that includes migrating herds of caribou. “It is a landscape lived in and lived with,” writes author and anthropologist William E. Simeone, who has lived there for 50 years. While parts of Alaska felt Russian, missionary, and other influences earlier, the upper Tanana remained largely isolated…

How they came to be by Jonathan B. Jarvis & T. Destry Jarvis The following excerpts from National Parks Forever: Fifty Years of Fighting and a Case for Independence (2022, University of Chicago Press), by Jonathan B. Jarvis and T. Destry Jarvis, are shared with permission. They are taken from chapter 2, “Alaska: Doing it Right the First Time.” Jonathan Jarvis was director of the National Park Service from 2009-2017. His brother, Destry, has worked in lands conservation for decades. While traveling thirty miles to another creek or valley in Virginia was an adventure, we vicariously visited wild country through the writings of Zane Grey, Sigurd Olson, and Wallace Stegner. We traveled west with Ward Bond on “Wagon Train” and experienced nature up close with Walt Disney. But Alaska called to us as the ultimate adventure. Little did we know that, one day, we would have the opportunity to not…

More than you see, fewer than you think peered around a boulder and there they were: a half dozen Dall rams bedded down, the nearest so close I could see my reflection in an amber eye framed by a curl of horn. They turned their heads to regard me but didn’t rise; instead, they gave what seemed to be a collective shrug as I settled in and raised my camera. I spent the next hours among them in the late August sun as they napped and grazed along the edge of that rock-strewn ridge, the air so still I could hear the echoing rush of the creek 2,000 feet below. That afternoon, still vivid after decades, explains as well as any why I came to Alaska: to meet wild animals in big, wild country. Pretty much everyone Alaska-bound hopes, even expects, the same. No doubt they’re out there, millions of…

Behind the scenes with National Geographic photographer Michael Melford Text by Emily Mount, photos by Michael Melford. Michael Melford popped open the door of the Piper Super Cub and looked out on an epic wonderland of snow, ice, and vertical rock. He and pilot Paul Claus were idling at some 10,000 feet on a flattish slope deep in the heart of the St. Elias Mountains. Suffering a few misgivings, he jumped out, plunging knee-deep into powdery snow. With a roar, Claus taxied downhill and dropped off the edge of the slope. Then all was silent. Melford was on assignment with National Geographic, photographing Treasures of Alaska, a guidebook. “I had read about Paul as the cowboy pilot of Alaska, one of the best in the state, so I trusted him,” Melford says. “I had to.” When Melford had asked for an air-to-air photo shoot with two planes, Claus replied, “We…

Past Disasters still haunt travelers “Could this whole world crack apart?” my three-year-old son asked me one day as we were walking along a beach on Coronation Island, a far-flung U.S. Forest Service designated wilderness area on the outer coast of southeast Alaska. We’d arrived here, to Egg Harbor, 90 miles south of Sitka, via our family’s small sailboat. “Of course not,” I told him. “But right here, I mean. What if there was the biggest tsunami ever? Or an asteroid?” I raised my eyebrows at him. “What makes you ask?” Admittedly, our position looked precarious from a distance—on one side of us was an archipelago boasting some of the densest brown bear populations in the world; on the other was the North Pacific, whose fetch is intimidating even on a good day. If there ever was a part of the world that might swallow a person, this fit the…

Appreciating Alaska’s parks and other public lands I live in Alaska because I was born and raised here, and it will always feel like home. But I stay in Alaska because it’s the only place on the planet with so much dramatic and varied wilderness. Alaska’s national and state parks alone total nearly 60 million acres. Some of that is right out my back door. Getting away from it all to play on public lands is as easy as hopping in my car and driving 30 minutes to a trailhead. Add a bit longer drive plus an air charter or water taxi, and I could be dropped off in the middle of nowhere to enjoy only my own company for days or weeks on end. Once out there, though, I wouldn’t really be alone, as so many wild creatures roam the land and water: grizzlies in Denali National Park and…

Appreciating Alaska’s parks and other public lands I live in Alaska because I was born and raised here, and it will always feel like home. But I stay in Alaska because it’s the only place on the planet with so much dramatic and varied wilderness. Alaska’s national and state parks alone total nearly 60 million acres. Some of that is right out my back door. Getting away from it all to play on public lands is as easy as hopping in my car and driving 30 minutes to a trailhead. Add a bit longer drive plus an air charter or water taxi, and I could be dropped off in the middle of nowhere to enjoy only my own company for days or weeks on end. Once out there, though, I wouldn’t really be alone, as so many wild creatures roam the land and water: grizzlies in Denali National Park and…

The Gift of Local Fare March brings new shoots of seaweed to Alaska’s southern coast, providing fresh nutrition at a lean time of year for wild foods. “Seaweeds are very nutritious,” says Vivian Faith Prescott, a lifelong Wrangell resident and author of My Father’s Smokehouse, a book on traditional Alaskan foods. “And they’re easy to gather.” Prescott says seaweeds have been a reliable staple for as long as people have lived on Alaska’s coast. She says spring is the best time to gather them. “Like some other plants, seaweeds can get stiff and lose their flavor later in summer,” she says. Prescott collects several seaweeds, including ribbon seaweed (Palmaria mollis, called k’áach’ in Lingit) and popweed (Fucus gardneri, called tayeidí in Lingit). But she says many species are edible and recommends Common Edible Seaweeds in the Gulf of Alaska by Dr. Dolly Garza as a resource. Prescott’s favorite vessel for…